My 500km Walk of Acceptance Alongside Visions of the Future

Or: A Personal Journey of Grief and The Acceptance of Burdens Alongside a Present Pilgrimage and Contiguous World Experience in the Age of Flight, a New Pope, and AI

In April and May 2025, I walked a part of the Camino Frances, about ~485km of it over 22 days. This essay is divided into 3 parts: my personal journey of walking it (through grief and acceptance), how the popularity of the Camino signals the future, and some practical lessons from a long walk like this.

My Camino of Acceptance

From loss to being lost, grief yanks us out of our life path and drops us in the middle of nowhere. Wracked with the pain and fear, we scramble for the familiar: a well-trodden path full of meaning to guide us back. Criss-crossing over unknown territory we align with the likes of family, friends, loved ones, work, fitness, religion, escapism, doomscrolling, drugs, co-dependency, strangers, and self-destruction. Some somehow blend it all, choosing to live it like a sunset during a thunderstorm: facing the torment alongside the new and unexpected beautiful freedom of being where you never hoped to be. Never waste a good crisis, they say.

For me, my path of grief followed the metaphor: a literal walk. It’s on my walks, on routine mornings in my neighbourhood or distant wanderings in far-flung cities that I’ve often found my guides and my meaning.

And so, I went to Northern Spain, because, alongside its wheat fields and mountains, tortillas, bocadillos, cafe con leches, and vino tinto over communal dinners, there's one inevitability on the Camino de Santiago, the pilgrimage of St. James to Santiago de Compostela: people will also ask you why.

Why are you walking the Camino?

Through the meandering stretches, in having conversations with myself and others, it might help me find my way back. To paraphrase Speed Levitch: on really romantic sunny Spanish days, I hoped to walk long stretches with my confusion.

Why are you walking the Camino?

You'll hear answers like:

I'm Catholic.

I just had to do it.

I don't know what I want to do with my life.

I want to prove to myself that I can do hard things.

I'm processing grief.

I want to do this while I can.

I want to just meet people.

An adventure!

I'm just wandering.

The wine and food! The nature.

It called to me and I have to find out why.

And through those answers you’ll understand how people are walking it: from big tour groups booking out weeks ahead to the minimalist pilgrim wandering into a town with no plans and knocking on the door of a donativo (donation based, usually maintained by a religious group, containing minimal amenities). People will walk every step with their entire home on their back. Some will taxi or bus or skip parts of it. Some will come for a week, some for 40 days. Some will come back. Some quit. Some due to pain and some just actually wondering why they weren’t on a beach instead.

For me, my answer was threefold: I love walking, I want to process the grief of my divorce, and lastly, like any crisis, I hoped to not waste it, in search of a reset to what I value in life. I (mostly) loved the path I was figuratively walking, but in finding myself in unknown territory, it offered me the opportunity to look up at the world and not at my feet. I had moved countries to be with someone I loved. Just who was I now? And where was I, truly? And where was I going?

When I usually walk, I do it both out of the meditative routine, but also to be surprised by the everyday. During my walk on the Camino I knew I'd see beautiful vistas, cute towns, and magnificent churches.

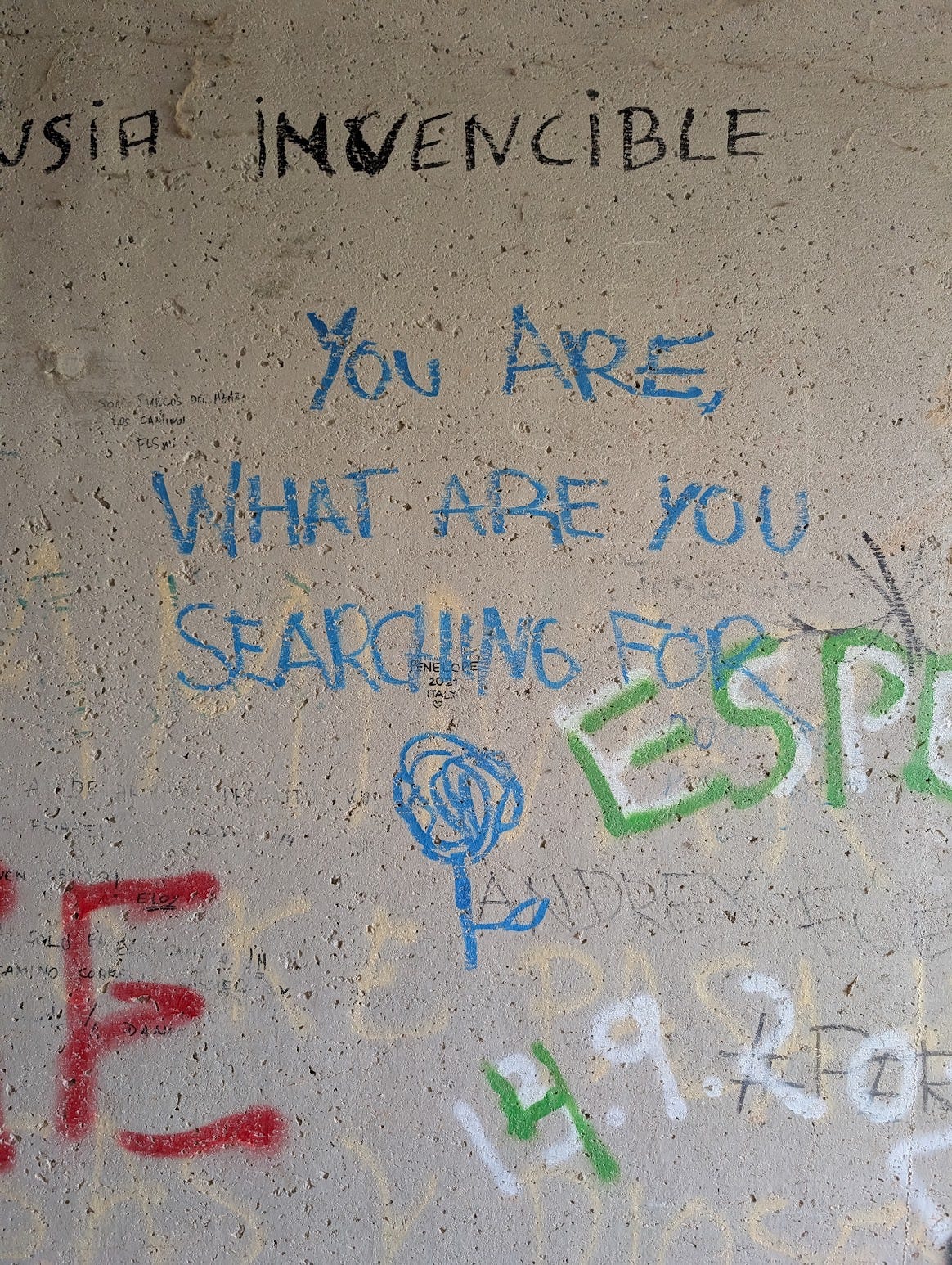

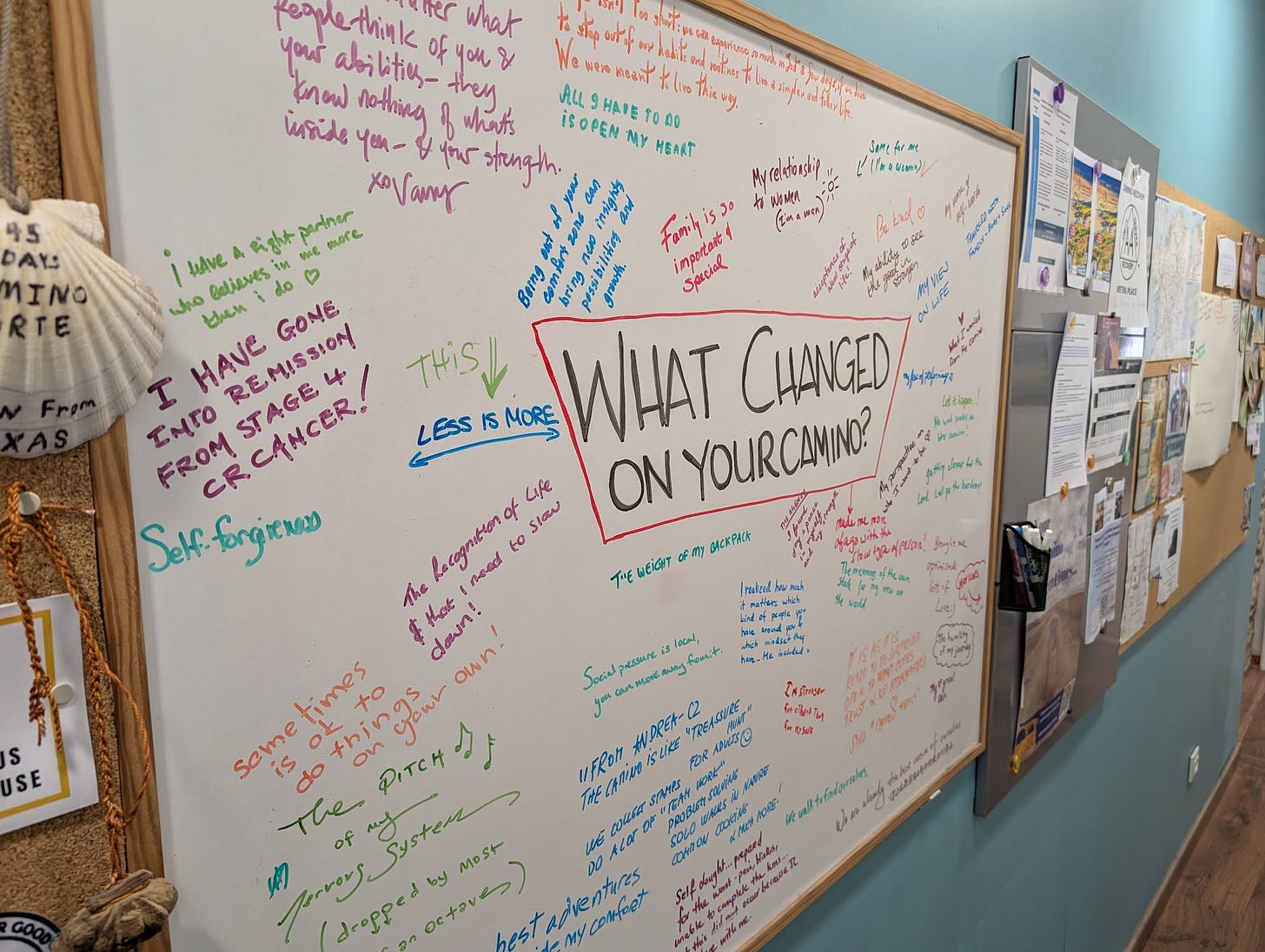

I was, however, surprised at things like: the interesting graffiti under bridges, the stark difference in the decay and renewal of small town Spain, and how far and close everything felt when you walk hundreds of kilometers continuously.

And, so, spiritually, even though I knew I’d be grieving, I did find a new surprise.

So, yes, I did grieve. I silently cried most of the days that I walked, counting my luck, because if it was the peak of summer, I'd likely have been far more dehydrated. It started in earnest on the third day, upon arriving at a cafe and behind a father-son duo playing guitar was a poster, that read: There is no other way, and there never was.

Struggling to finish my cafe con leche, I set off, and amid wild flowers around the corner, I cried. I cried through the end of the Pyrenees, through the wheat fields of Navarre, through the red clay and wines of La Rioja, over thousand year old bridges, and industrial entrances to towns and cities.

Despite the tears, the days were grand and beautiful. Blessed with little aches and pains, I could easily carry 8kg on my back and do 24km a day without serious pain. While others were physically struggling, hobbling, and patching up blisters with packs of tape, I was throwing out a Buen Camino to every stranger along the way. But, upon arriving at my stops each day, beautiful towns with deep history to them, the real grief and depression raced to catch up with me.

As you walk it, you tend to see the same faces in towns, albergues, and views. Over time, you develop camaraderie, and if you wish, you become attuned to this temporary family: your “Camino Family”. At the end of the day, seeing a familiar face was a delight, even though you hadn't seen them in 3 days.

But, I had my own unintended spiritual Camino family. My depression too was walking the Camino and at the end of day, it caught up with me. I felt immobilized and overwhelmed and found that the only way to medicate it was to meet people. Wonderful people whose stories of their own grief, struggle, and turning points in their life were far more profound than mine.

The walking for me, turned out, was an escape each day, experiencing deep peace and bliss when my feet followed each other. The real struggle however, was stopping. I returned to a hostel or a room filled with not just the task of dealing with my depression, but also that I had to keep booking ahead.

I wasn't a part of a tour group that booked everything ahead or a minimalist that wanted to arrive in a town with no plans. I didn’t want to rush my walking, and during peak times, it can become what they call a “bed race” (get up early, rush to the next town). In not wanting to delay my walk for a quieter time of the year, it became a necessity to think ahead a few days at a time.

But, then, I should've known, besides the depression from grief, another member of my personal Camino family eventually showed up: the avoidant planner. I don’t like to plan some parts of my life because when I do plan them, I over plan. I do too much of it, and then it takes me out of the rest of my life.

It’s the medium term planning. I love planning the day-to-day, figuring out what to cook for dinner, doing household maintenance, taking the car for service, etc. I enjoy long term planning too, setting my life on 5 year trajectories: starting and finishing big projects (like my latest novel, having taken 20 months to draft 2) or training for a new running race. The day-to-day is a routine that can disappear into the background and the future is shaped by persistent discipline.

But, it's the messy medium life I struggle with and dismiss. It is: call an old friend, plan a vacation, organize a group dinner in two weeks, schedule that call with a potential industry partner, and start a Dungeons and Dragons campaign with friends. When planning a vacation, I have to read all the reviews of 10 hotels to make sure it's great. It's debilitating and takes me out of the other two parts of life: and then, it ends with an oh no, I planned the entire afternoon, so sorry, I didn’t have time to go get groceries, we're having takeout tonight. And, oh no, I planned the entire afternoon, and now I didn't write and work on my new book at all today.

I dislike it and it’s something I’ve not just critiqued myself about, but it’s also people close to me that have pointed out. In reality, it’s just not that hard, and over-planning is far better managed by simply dealing with problems when they arise, rather than pre-empting them. So, the answer is actually simple: plan more, it’s not that serious, and relax. But, old habits are well-trodden paths. And so, having to also continuously book something every day alongside the walk itself and my grief, got the better of me.

I wanted to quit. Doubts filled me. I wasn't really sure why it was a smart idea to challenge myself in this way on top of my grief of my divorce. But the walking itself was so delightful and when I planned the trip, I deeply wanted to walk two sections of it: over the Pyrenees and the empty, flat Meseta. The Pyrenees was behind me and so I continued, setting Leon as the checkpoint. There I'd decide to end or continue. It was made easier because I knew, in part, my depression wasn't unique to my walk. It would've knocked on my empty apartment door in DC too. It *is* nicer to be depressed in nature and quaint towns in Spain than a space that held so many memories.

And then, the surprise arrived…

While I remained physically fine, my mental pilgrimage continued to gnaw at me until one afternoon I walked into the common area of an albergue and saw friendly faces I had met in the days prior. The town I stopped at was past the usually suggested stages because I found the accommodation looked nicer and it would break two long walking days with a shorter one in the middle.

There, in that small town in Spain, a new friend told me that many of the people followed my lead when I told them I would be walking further than most. They were happy. Quite a few of them were. Simon, they said, just tell us where you're going next. You seem to know what you're doing.

My forced overplanning helped others. Here, something I’ve come to hate about myself, unintentionally, became a gift. Upon arriving in Logrono, a major city, we were suddenly stuck in the mass blackout across the Iberian peninsula. With not much to do, I wandered around. With the locals closing up shop, it was easy to spot fellow pilgrims I'd met, lost, looking down at their phones hoping the Internet would briefly come back on to guide them on their way. Because I had researched most of the places to stay in the city, I led some of them to their hostels. Again, my burden, now, a gift.

It's not that my act of service was unique and astounding. The camaraderie is bountiful, with pilgrims sharing food, tales, recommendations, and aid to one another. Another common refrain on the Camino is that: “The Camino provides”. We’re “Camino Angels” for each other. In my own context, however, it felt profound.

Unintentionally, I found that perhaps the parts of ourselves we might be most self critical about, isn't something that we're always supposed to conquer or overcome. Instead, when we practice acceptance and self forgiveness, we turn off the inner struggle. Then, we can do both: become better with grace at what we want in life, and secondly, find a way to turn that burden into a gift. I need to plan more because I want to. I've seen what value that's given me in life from people that did it for me. Plan that vacation. Call your parents. Start that book club. Book that restaurant you’ve always wanted to try. Do that road trip with friends. Throw that birthday party for your dog. When you see a self-perceived weakness (I don’t like medium-term life planning) turned into a gift (my over-planning, helped others), it becomes easier to change. I don't always have to treat it as a burden, when I've seen it as a gift.

As the flatness of Meseta spread into the horizons over green fields, red poppies, and yellow flowers, so too did the my internal oscillation. You never know when you might see someone again on the Camino, not knowing whether they're ahead, behind, or left. Your Camino family changes over the course of your walk. And so did my internal Camino family. On some days, I didn’t cry anymore. On some days, there was only peace. On some days, the depression came back, having clearly taken a rest day in some small town and then bussed ahead to catch up. But, overall, it became easier.

I felt better, eventually having my mental anguish be replaced by physical ones, picking up blisters and aches after having been free of it. It actually felt good to feel my body and not my heart. They say that the first third is about the body adjusting. The second third about the mind. The last third about the spirit. Mine didn't seem to follow the rules, having struggled spiritually and mentally, only to feel my body, later. As I came closer to Leon, I however knew what I needed more of right now. The walking, while beautiful was keeping me from the real road I needed to walk: to see my family and more importantly, to go back and move on from a chapter that ended a few months ago. While I had only been in the Camino for 3 weeks, I had been on the move, literally and figuratively since separating. For 5 months, I had not slept in the same bed for more than 2 weeks, nevermind a new one every night for 3 weeks. It was time to stop walking the Camino and instead continue to walk my life that abruptly ended six months ago.

I did doubt myself though. Is it a failure to stop? By having the means to stop and to come back in the future, am I just privileged? I didn’t need to stop (life obligations or physical), it’s because I wanted to. Self-critique and fear of judgement from others rises in these moments. It’s an age old question asked in so many life situations: should I stay or should I go? And we never truly know the answer. It’s especially harder when you tangle perceptions of self into it. Most people want to be people who don’t quit. But, for most of my life, I usually found myself at the opposite end: staying longer than I should in situations due to a likely self-inflated sense of importance (people need me) and being generally conflict avoidant. Quitting, for some, is sometimes a harder choice due to various beliefs about being reliable, loyal, and dependable. When I spoke to people about stopping in Leon, I found that most were accepting. A handful encouraged me to continue. Some were disappointed that I’d stop. But, I found an interesting trend. The older folk were the most relaxed about it. The younger people had a far more attached relationship to what this pilgrimage was supposed to represent to them. And, I think that’s generally true of life. The longer we walk it, the more we become less attached to it being a specific path. Acceptance of things that happened and acceptance of things to come become more common. It felt particularly more pronounced when a fellow pilgrim I met announced in a “Camino Family” group chat, that near the end of his walk a new friend of his on the way, didn’t wake up one morning. Sadly, they passed away in their sleep. We truly don’t know when our final walks of life will be and the cliche holds true: if you knew this was your last walk, you would follow the advice of the Camino being preached throughout. Walk it your way.

This does not mean that one shouldn’t challenge oneself and sometimes hold oneself to higher standards, when you’re young or old. But, I think life would be far easier if we took that saying into the rest of life: let people walk life their way. What they need is not necessarily what you need. Sometimes people want to be encouraged to continue, and sometimes they want to be told: Hey, it’s okay. You’ve already done a lot. It’s time to rest. You can leave if you want to. Let me help you.

It also doesn’t mean that in some life situations we won’t regret staying or regret moving on. Reasonable self-doubt is healthy. But, we *can* choose to fight fewer battles. Acceptance gives you back some of your energy to actually just focus on getting stuff done. How many times do you think self-doubt only served to stop you from taking action? To put one foot in front of the other instead? That voice really does not have to be so loud.

And so, still interested in seeing the end, I took transport to the final stage, and walked into the square in front of the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela not with a jubilant and joyous celebration, but with a quieter peace and acceptance. I arrived after 485km and 22 days of walking but, even though my tears watered the plains of Spain, my journey wasn't over.

A tradition of the pilgrimage asks the pilgrim to bring a a stone, ideally from home, to leave at the foot of the Cruz de Ferro in the Galician mountains. It symbolizes the letting go of a burden that you carried. And so, I took a small pebble with me from a nearby park in DC, hoping to symbolically close a chapter of my life by doing the same. I never reached Cruz de Ferro, but as grief guides you to meaning, I felt that conclusion was apt. You aren’t always supposed to let go, to conquer, to overcome, to do the *hard thing*. Instead of having left the pebble in Spain, I took the pebble back home and placed it back where it came from.

We can keep what feels like a burden and treat ourselves with grace, kindness, acceptance, and self-forgiveness. And maybe through that, we not only learn to be better at it, but also hope to be lucky to see it one day used as a gift.

I walked ~485km over 22 days, but I stopped. Now, I hope to medium-term plan more in my life. And after staying in a new bed for 22 days, I've come to accept that you really don't need to read every review. There’s more work to do. I will still grieve and cry in new places that isn’t the plains of Spain. I will still face depression. I will still struggle to change and turn off the internal battles. I will still struggle to piece together a new life. Old habits are well-trodden paths, after all.

But, now, I will remember the tiny stone sitting alongside a tree in a small park in DC, the burden that travelled through Spain with me, and think back to the surprising feeling of peace and acceptance I had discovered. When the pain and fear comes back, I don’t have to scramble. I can turn these voices a bit quieter and remember that quiet peace of a Meseta sunrise. The start of a million steps in returning from grief begins with one crunching gravel step in front of the other.

To all the people I walked with. Thank you for listening. Thank you for the acceptance.

Buen Camino.

Simon

2. A Present and Contiguous World Experience in the Age of Airplanes and AI.

As we walked in a snaking procession ever west, on colder sunny mornings, I'd look up over the yellow flowers and see white streaking airplanes against the soft blue skies.

In medieval times, the previous height of the this journey, pilgrims counted their blessings if a horse or carriage helped them along to Santiago de Compostela. Today, we walk not because we must, but because want to. And more and more are doing so every year. This trend is occurring alongside the resurgence of physical goods and run clubs. A desire for a life of physical presence and being against the backdrop of algorithms and the impending sweep of generative AI in everyday life.

The day before I started, the Pope died and I imagined that some of those planes might carry a cardinal to the conclave in the Vatican. Part way through, one late afternoon, as the church bells rang through northern Spain and the white smoke erupted from the Sistine Chapel, it was thus inevitable that one of those planes did contain Pope Leo XIV who chose his name in part as callback to Pope Leo XIII's reign during the industrial revolution and the impact that it had. Today, it's about the question about how we're going to live and be in the age of AI.

On the walk through Spain, I thus saw more of that future. And the prediction is simple: the acceleration of complexity will increasingly go hand in hand for a desire to physical presence and being.

One of the most unique parts of walking the Camino is that it lowers the barrier in connecting with others. Because everyone is on the same journey, everyone is walking, and all the pilgrims are easily recognizable, a simple hello opens up to immediate conversation. And because it's accepted that you “walk your own Camino”, it's also (mostly) easy to exit and move on if you don’t want to have a conversation. It’s both great and unnerving that I had longer conversations with people I met in those 3 weeks than what I regularly do with good friends and family. People from Korea, Netherlands, USA, Belgium, Singapore, UK, South Africa, Brazil, Canada, Australia Uruguay, all over the place! It remains bizarre to see the same people again in new cities. A bubble… More on this later.

The ease and acceptance of the community, often called a “Camino Family” is something that's readily missing from modern urban life. There was a retreat away from neighbourliness and people clearly crave that again. But as with the metaphor of walking-to-planes, what was a necessity (neighbourliness) now becomes an active choice. The algorithms and AI won’t stop flying, but we’ll also want to walk again (literally and figuratively).

As generative AI collapses process, it will accelerate everything, including our inability to discern authenticity and sincerity. But nothing is more authentic than a slow conversation with someone else. While some people are unable to discern what's real (see boomers and AI slop), this change will be driven by those who can afford to opt out. It's not the same as the turn of the century where you couldn't avoid getting an online presence. The difference now is that after saturation, the harder part is to switch off. The ability to have a rich social life without a digital presence is increasingly seen as highly valuable and socially desirable traits. It signals high status because there's no reliance on platform mediated sociality. These people will drive the growth to opting out. They will prefer an in-person meeting over the likelihood that an email could’ve been filtered through an LLM.

But the question is, what does this practically look like? When people tire of algorithmic social networks and a dead internet occupied by generative AI, what will be desirable is what will be hard. When we can't trust anything online, we will trust what we can see and understand again.

It looks like:

- The continued surge of physical activity. This is buffeted by GLP-1s where when it becomes easier to be healthy, it will be harder again to be strong. Run clubs, ultra marathons, walking, dancing, gym culture, padel, pickleball, etc.

- Physical expression through physical products: a physical video store opened again in Brooklyn. It's vinyl and printed-books-as-aesthetic.

- Clubs. Especially clubs that feel like a neighbourhood. Running clubs feel like neighbourhoods because you can always leave. Meetups in physical spaces will grow but not as much as clubs that afford the ability to leave. Think walk-and-talks vs meetups in a bar. It’s the organised unorganisedness that matters.

- Pop-up Cities. Not unlike a Camino… Pioneered in part by crypto where relationships were digital first, a crowd would travel and meet in person in cities all over the globe. By co-opting the conference format, it eventually grew into being a pop-up city, which is what most people actually wanted from it: informal socialisation around physical anchors. It's almost if they live ambiently nearby, you just happen to bump into them in different world locations.

- It's podcasts as the most popular media, exporting the conversation.

- It's the surge of bathhouses (like Othership) in the non European West.

It’s ultimately about primacy. From which domain does your world hang onto? Is your physical life determined by the digital or your digital life informed by your physical world? Since about 2014/15, my world changed. My physical world hung from my digital world. Getting into the crypto industry necessitated it. Online was the primary space. Conferences in cities were a bonus to the digital. Conversations were about what happened online.

The alternative is a life where any digital engagement is a bonus to a physical life. It’s using digital tools to primarily have physical experiences (which I feel that pop-up cities do a better job of). I think without the arrival of AI this would’ve happened anyway, especially as millennials age out of the social media they grew up with. But, now, with AI, this accelerates. Platforms come and go and many people have grown to give up their social agency to them. I believe we’ve already seen this change, and it will continue to accelerate.

People desire a return to physical primacy buoyed by digital tools. Not a digital life that determines their physical agency. I think it’s an exciting time for reconnection away from algorithms and platform-mediated sociality.

People will continue to go outside. People want to walk.

And what does a world look like where you use more digital tools to create a better outside? It’s coming faster than you think. And in all honesty, it feels exciting because it feels like it brings back mystery to the world. The not-knowing. The wonder. Not everything needs to have an eye on it.

3: Practical Takeaways From Walking the Camino Frances

There’s a lot of articles, videos, and guides on people walking the Camino Frances. Despite reading a lot, there were still a few things I wanted to share.

It’s really well catered for. I went out with a 34L Osprey bag and rarely had to carry food with me. In the spring, I also never needed more than 1L of water.

Speaking of spring. Constantly debated whether I should bring a sleeping bag or simply a liner. On the coldest night (-2c), I was in a 200-person dorm (1st night in Roncesvalles) and even with the window open, it was still too warm for a sleeping bag. Much further down, in a chilly night, I thought, this was it! I opened up my sleeping bag and once the room filled with people, it was already too stuffy! 😅 If you’re sleeping in albergues, it’s often warm enough that you don’t need a sleeping bag in spring. So, I carried an extra 500g for not much use. I can’t imagine walking this in peak summer. It must be unbearably hot in the albergues.

Another spring item I didn’t need: headlamp. The sun rose at 7am each morning and I rarely left before then. Never needed it. Even in the morning in the albergues.

My favourite item: My Ozlo Sleepbuds. Expensive, but it meant that I slept soundly every night (besides the stuffiness). Never heard *any* snoring or rustling of beds, sheets, and people.

It’s hard to keep on weight. I usually don’t have a big appetite and I was eating (and drinking) a lot of carbs just to try keep pace. But 4-6 hours of walking a day is a mega fat burner.

I walked in Altra Lone Peak 8s. Was very nice. With a toe-liner sock + hiking sock over it. Held very well for most of the trail, except the last few days where I started to develop a mild blister or two. But, vaseline and lambs wool helped keep it from getting worse.

I did bring Xero hiking shoes as both: after-walk + shower shoes AND as an emergency backup in case my hiking shoes had a problem. But, it was too much. Hard to use in a shower and when it got wet, the bands stayed wet. Would rather just bring like super simple sandals that can be used in showers and outside. No need for bulkier after-walk shoes. And considering that I know that my Altra’s can do the distance, I don’t need a backup shoe. As I said as well, it’s so well catered for, that even if you need new shoes, you can just survive to a big-ish town.

*Do* bring walking poles. Takes off 10-15% off your legs and feet and very useful in tricky terrain. Especially in muddy areas when you have to balance yourself while have extra weight on your back. I bought some at the start and then donated them to the Pilgrim’s House at the end (since flying is cumbersome with them).

There’s some quite eclectic accommodation options. I stayed in an igloo/dome one night! Another night in old monasteries or churches. Do try and find the unique accommodation. You *can* just wing it, but I think you’ll miss out on the fun and interesting places to stay.

Some towns are super depressing. Some towns are really cute and awesome. Feel like this any rural town in the world atm. Some managed to reverse decline.

Bedbugs… I sprayed my bed gear in permethrin and used dry bags in my backpack (so that if something is contaminated, it doesn’t spread). I also put my backpack in its own bag every night to ensure it stays sealed. Truthfully, it’s a lot of work/effort to stay super diligent about avoiding bedbugs. I did see one, on arrival to a private room one afternoon (which was odd, it being during the day). Left me paranoid, and then never saw one again. I surmised it was due to a large bag nearby in the hallway that was shipped ahead. So, if you *do* ship your bags ahead, do seal it, because your bag is getting placed together with a lot of other bags. I didn’t hear others encounter bedbugs. But, it comes with the territory. Just something to be aware of, but not super serious to be a massive concern. Earlier in the season is better to avoid it.

It’s getting really popular as a thing. The Frances is well catered for, but if you want to avoid crowds, opt for the other ones, or go during a different time of the year.

Do the communal dinners when you can find them. Best parts of the trip for me.

You’ll meet so many people. But you don’t have to opt into being super social. People respect how people want to do it.

Ablutions? I rarely had issues. A simple trick was to drink water upon waking up (to get the bowels moving), pack up my stuff, go to the bathroom, and that was it. That being said, almost all cafes, restaurants have bathrooms that you can use if you buy a small thing from them.

You don’t need to know Spanish. But, it helps a lot. After my 1300 days of Duolingo Spanish, my listening improved dramatically. Twice, I had hoteliers explain everything in Spanish and I could understand. Very happy about this.

You don’t *need* to book ahead, even during peak times. But, understand the trade-offs. You might need to walk earlier to get a non-bookable bed in a municipal or donativo albergue. And sometimes these non-bookable options are impeccable (especially donativos). I think doing just a bit of basic research in each town you might stay at, helps to find the great places to stay. If you walk the average length a day (24km), you’re done by lunch. And then you have afternoons to decompress, rest, research, book, and hang out.

My shortest day (besides a rest day) was 17km. My longest was 45km. The latter broke me a bit. But, I loved it. My favourite times was when I didn’t actually conform to the Camino itself. It was when I did a 45km day and when I accidentally got lost one day. After mid-day the trails become far emptier and then it’s just you and the wide nature. The zone/flow is so powerful then. That being said. It’s actually quite hard to get lost because there’s yellow arrows and camino shells everywhere pointing the way. I was following an online suggestion for a prettier detour which led me astray.

I used a physical book/guide (the popular one by John Brierley (thanks Anna for the recommendation)). And then also relied heavily on the Camino Maps app. The book was for checking the day’s walk. And the Camino Maps helped plan distances when I didn’t want to stay at the recommended stages. Gronze is also a useful resource for reviews. That + Google Maps.

Rain jacket > poncho. The amount of times I had to help a pilgrim put on their poncho in sudden rain? A lot. Yeah, rain jackets are better. 😅. Even if your pants get a little wetter.

Get used to Spanish eating hours and shop times. Thins do close in the afternoons. Long lunches (to 4pm-ish) and then dinner from 8pm+. Some places offer pilgrim-friendly hours (from 6pm). Sometimes, I just had a lunch on the walk and then a late lunch as dinner instead. Waiting till 8pm sometimes was excruciating. In one town, only having 3 like restaurants, one that had reasonable hours was unexpectedly closed and so many of us just went to the supermarket instead for cheese, breads, and fruits.

Speaking of hours. Don’t trust any of it. What’s online is sometimes wrong. Places are just closed, just because, sometimes. Hours change. So, only way to truly know is to check the doors of places and then hope it opens on time. A good lesson in taking things less seriously.

I stayed half the time in albergues and half the time in private rooms. Albergues are cheaper and are great for connecting with people, but sleep is tougher. Private rooms are great for crying. 😅

Now that I’ve gotten a hang of the general vibe, I definitely want to do more of it, hopefully in a better mental health space, and I would actually like doing it with someone. Doing it solo is totally fine. Many people do. But, it’s something I’d love to share with a friend, partner, or family. There’s so many great walks/hikes and it feels like the world has opened far more than I ever knew.

Thanks for reading, friends. Please enjoy a cat.

AMA if you’re curious about any part of the journey.