Owning the Memes of Production

What Memecoins Can Teach Us of Access to Ownership. Also: GPU Organs, Rings of Power S2, and Builder’s Remedy

I'm socialist in the sense that I want more of society to own more of it. Not just in a welfare state sense where taxes pay for public services, but in a more classical sense: having more people *directly* owning the “means of production”. Capitalism works best when more people own capital.

In crypto, since Dogecoin’s appearance in 2013, internet memes have grown over time to form a larger part of the market. As scaling and UX has improved it's become as easy as ever to launch any token and since 2021, it’s seen a resurgence. > $50B of value.

To some, crypto doesn't make sense, nevermind memecoins. It looks from the outside like a zero sum gambling game where scams and grifts promise retail investors mega returns only to fleece people out of their money. This does happen in some capacity, but there's also a group of people who enjoy this financial PVP and if you dig deeper why, you might see lessons to inform how to improve modern day economic systems. Sometimes you have to look in unique places to find solutions.

In this video, Murad, explains why people enjoy trading memecoins.

It provides two core promises:

- A community. It's entertainment, it's funny, and sometimes thrilling. It's very social, allowing people access to a community by merely buying a memetic ticket.

- Over time, it's become fairer. Access to wealth creation is more equitable.

While the community aspect isn't for everyone (hey, trading animal derivatives or 4chan-esque malformed political coins isn't exactly mainstream appeal), the latter provides insight and an indictment over how we've come to structure access to wealth creation today.

Many successful memecoins have what's seen as 'fair' entries. In other words, it avoids enriching a few, usually seen as headless (no one leader or group), and ongoing rules are hardcoded and mediated through transparent and verifiable smart contracts. A rug pull (sweeping you out under your feet) is less likely as a result.

Thus, part of the appeal comes from having fair and easy access to wealth creation as an entertainment product. If it's launched fairly (with no one group being the head of it), it's also likely that there's almost no regulatory scrutiny. This means that access doesn't discriminate on where you are, and who you are. Once inside, it doesn't matter if you are a wealthy fashion designer in Manhattan or a subsistence farmer in the Philippines.

The reality is, today, most forms of wealth creation is only accessible to the wealthy and has increasingly become more difficult to enter. For example, getting access to liquidity is hard, certain rules favor the rich, and public access to markets has diminished.

Problems of Liquidity

Not everyone is where the liquidity is. It's harder to start the same tech business in South Africa vs the USA, for example, simply because there’s more money in the US willing to risk it on new ideas. Starting a business isn’t easy and increasing forms of compliance has made it even harder.

Problems of Access

Even if you are in the US, you can be excluded from access to an investment because you simply don’t have enough money. Under some conditions, when companies sell securities, only rich people are allowed to invest. For example, under rule 506c in Regulation D of the Securities act, if you want to broadly advertise an investment for a private sale, only accredited investors can invest. If you are poor, tough luck. By nature, this excludes people from access, even if it’s deemed necessary for the functioning of an ‘orderly market’.

Public Markets

Let's say you can't be an accredited investor. What forms of access do you have to invest in wealth creation? Some private opportunities do exist in the US, otherwise it’s mostly public markets: owning stocks directly, ETFs, bonds, etc. While companies have made big returns after listing, most of the order of magnitude gains happen prior to listing.

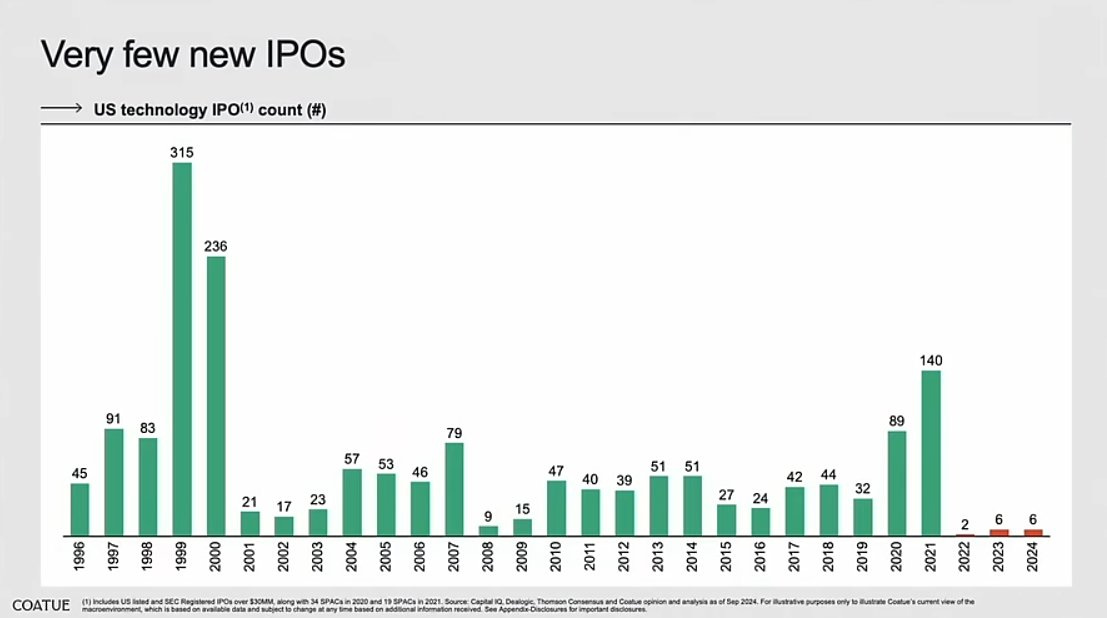

Unfortunately, if you do want to invest in a public market, in the US, IPOs are expensive and have since 2022 lost steam. Just the legal and accounting costs on average were >$2m in 2019. In the US, IPOs have been on a decline.

In terms of total listed companies, it doesn’t look that much more promising either. While I tried to get worldwide data, the world bank data had a strange spike for China which I couldn’t verify where it came from. Thus, unverified it looks like this, globally:

But, more specifically, the USA looks like this.

Globally, it looks like as the rest of the world industrialized, access increased per capita in some places, but in a developed country like the US, had stagnated. Will this trend continue or be the norm when more countries have caught up?

So, now what?

Understandably, an approach that many might wish when faced with these conundrums is to deregulate, but it comes with trade-offs. When one looks at financial regulations, its intentions are to ensure orderly markets, investor protections, and maintaining a relatively healthy investment environment. By adding these layers of compliance, it derisks. That is true, to some extent, and it’s likely that money will flow to places where investors have more certainty, even if it’s at the cost excluding many from access to these opportunities.

Deregulation across the board might help in some ways to improve ownership, but it can also derail a lot of good faith attempts at wealth creation along with it.

The answer isn’t necessarily to deregulate but to rethink what prudent investor protections look like in the modern era. Much of it was designed and continues to be designed for the pre-internet age where you had issues like bearer stock certificate fraud. But, if one might want to rethink how to provide sane protections without adding too many barriers, what that would look like today?

One place to look at is memecoins.

In the financial PVP of memecoins, the cream that rises to the top shows that one can reconsider getting access to wealth creation opportunities much earlier AND retain reasonable investor protections by putting the guardrails in different places as to where they are today.

It’s saying that:

Don’t protect people by excluding them. Protect them through certainty in novel ways.

Ensure transparency not by a requirement of mass administrative compliance and documentation (which costs a fortune), but through code that *can’t* allow malfeasance.

Maintain order of the markets through a systemic lens and not a focus on personal impact.

For example, much of the recent popular memecoins all start from a token bonding curve. This mechanism (which I helped popularize) creates new supply by initially creating a reserve and allows participants to buy into and sell along a price curve, transparently. It means that there’s not one specific entity receiving the money. It’s held in common for one purpose only: liquidity. Then, when it hits a threshold, it ‘graduates’, capping the supply and putting this reserve into an automated market maker providing ample liquidity for the market.

It means that:

Investors don’t have to worry that someone is going to run away with their money.

There’s no insider club. Everyone has equal access (just depends on your timing, much like public markets).

Guaranteed liquidity being available earlier reduces odds of manipulation.

It’s all transparent and public.

Under many conditions, this template allows earlier and fairer access at a scale that could still protect smaller investors. It doesn’t entirely remove scamming and grifting, but is an example of moving the guardrails to a different position.

Yes, Cool, But Maybe Not Everyone Should Invest?

I find it condescending to believe that if you aren’t rich, that you are immediately seen as incapable of understanding risk. That being said, in this exercise of eradicating class disparity to access to wealth creation, there’s understandably an aversion to an over-financialization of the world.

That tension is a tough one to thread: if you live in a capitalist society, how do you ensure that people can create wealth for themselves without wealth taking primacy over *all* relationships that exist in it?

That in itself is likely its own topic. For example, recent research shows that legalized sports gambling increases debt burdens and subsequent bankruptcies. Credit scores in states where it’s legal dropped 1%.

In this, one might ask the same question: should people be allowed the freedom to take these gambling risks? Yes or no? In one of the studies, even though bettors spend more than usual, the average is skewed by a small percentage.

However, most of this betting comes from a small set of high-intensity bettors. The top tercile of bettors (based on total betting deposits) bets an average of $299 per quarter, or 1.7% of their income, while the bottom tercile of bettors only bets an average of only $1.39 per quarter.

This is similar to data from New Jersey:

In New Jersey, 5% of bettors place nearly 50% of the bets and 70% of the money. Gambling sites’ profits come from extracting losses from those bettors — just like a casino.

An age old question results: how do you square away personal freedom when something legal affects a small portion of people, drastically?

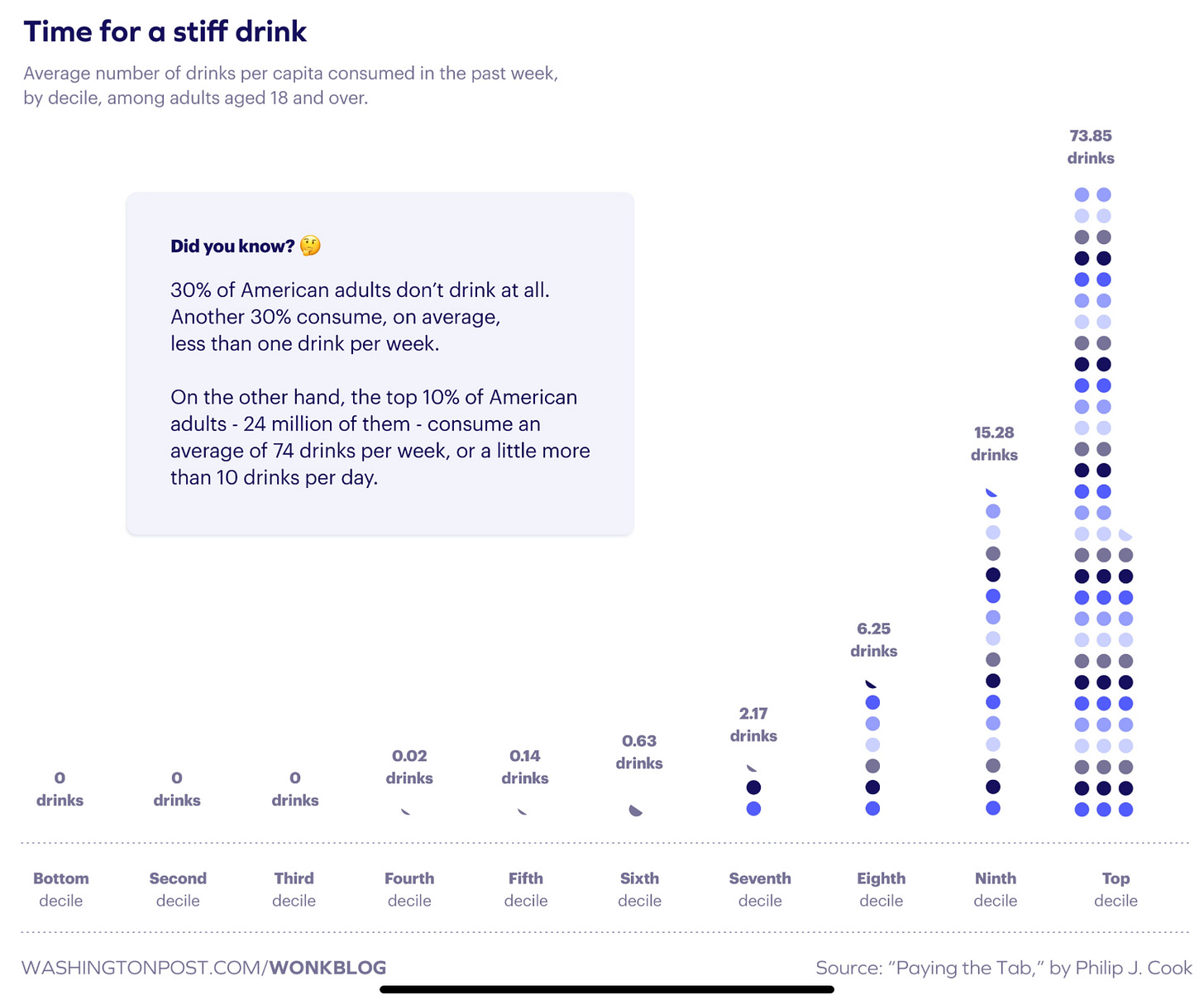

With alcohol, many countries look like this:

Society might view this differently if those personal freedoms of the top decile result in systemic spillover. Alcohol *is* a big, systemic problem, where the top decile results in drunk driving accidents, abuse, and intolerable public disorder. Yet, it remains tolerated. In other instances, like gun control where most owners might be responsible, it’s not as well tolerated due to the tragic nature of mass and indiscriminate gun violence.

Thus, some degrees of personal freedoms that are fine at an individual level manifest instead as a compounded societal problem. In that sense, financial regulation for some isn’t just about ensuring orderly markets, but to also temper the amount of transactional financial activity from everyday life. I’m sympathetic to that take and understand why some societies want that.

And so, whether we *want* a world with more financialization is different to ensuring that the one we currently have remains accessible. If you’re okay with the idea that we should increase access to wealth creation and the trade-offs that come from that, we can learn from memecoins without resorting to broad deregulation.

Capital and liquidity is flowing into memecoins in part because the guardrails built in the legacy financial system was built in an era prior to the internet and crypto. In the pursuit of ensuring orderly markets and investor protections for an older era, it’s actively promoting more inequality. By moving the guardrails to the 21st century, we can hopefully reduce this class disparity of access. And thus, more of society, can own the memes of production.

Bonus Content!

Back in travelling mode this week, enjoying a wedding of a good, old friend! Also, being back in California is so nice. I love the weather so much. Makes me feel at home with how much it sometimes feels like Cape Town. Puts a big smile on my face without even trying. Dry, warm, blue skies. :)

📚Reading - Haruki Murakami - Kafka on the Shore

Got some reading in on the flight. About halfway through and enjoying the journey. :)

📺Watching - Rings of Power S2

Finished watching it. Enjoyed it! Better than S1 for me. More excited to continue watching it! One thing that actually lifted my mood substantially about the film is some of Bear McCreary’s great compositions. Howard Shore made such an iconic soundtrack for the films and I adore that some of the musical themes and motifs from Rings of Power will attain a similar feeling.

🏃♂️Running - Settling Back In

Post half-marathon, I haven’t focused on increasing my mileage by much and just enjoying some maintenance running before getting back into the rhythm of improvement. With it getting cooler, it’s also so much nicer!

💾 Links

GPU Organ

Mat & Holly have a new exhibition open at the Serpentine Galleries in London. One part of has a set of GPUs playing an organ. Haunting.

It’s part of a larger exhibition where they continue to play with the interesting overlap of AI, data, and ownership. The organ plays a diffusion model of volunteered data from choirs and with Serpentine created a new model where data for AI training is owned in the commons. If you’re in London, go check it out!

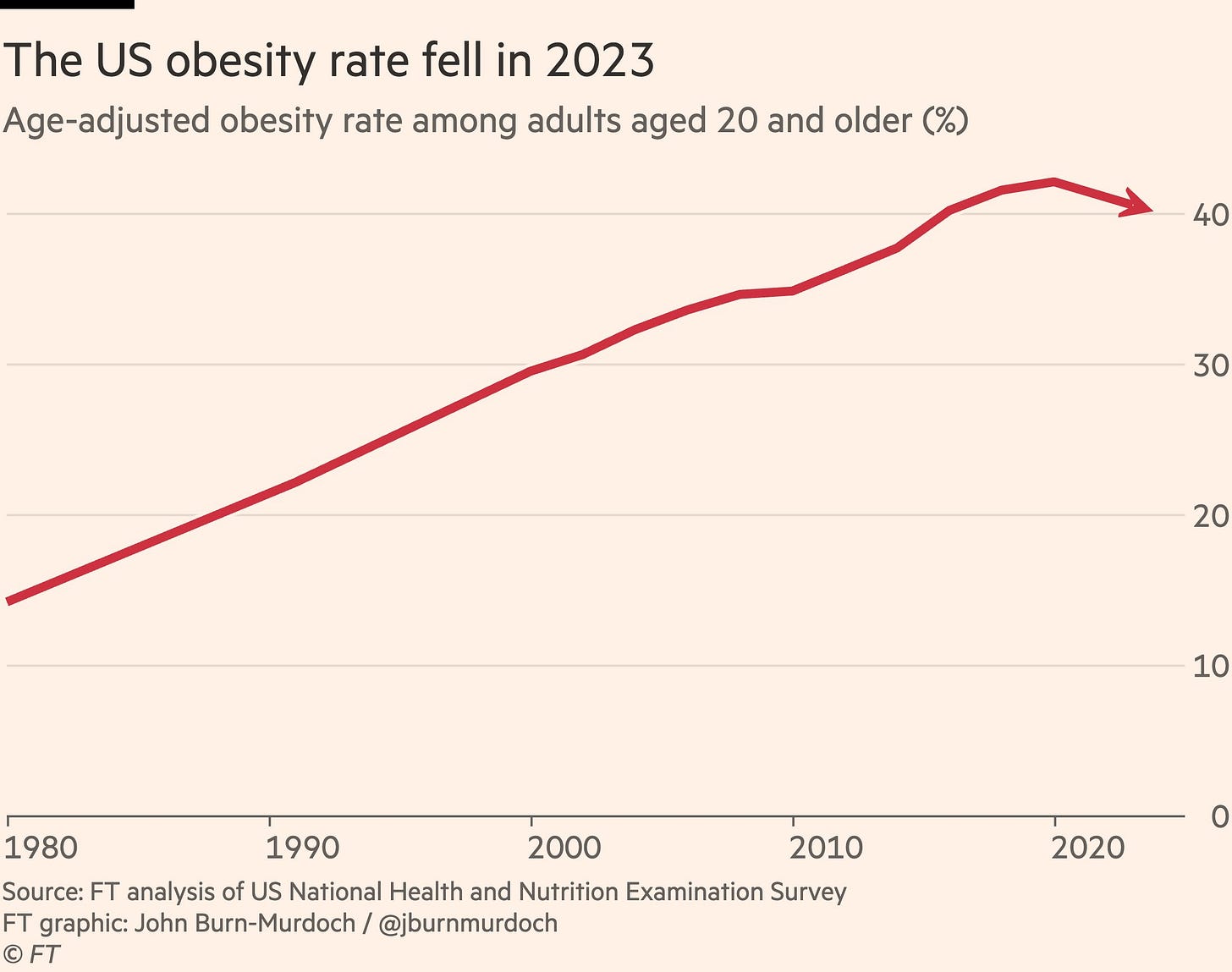

Peak Obesity?

The US has hit peak obesity. Part of the explanation comes down to Ozempic, but in part, I think there’s a general cultural trend towards fitness: running clubs are high, people are drinking less, and fitness podcasters are quite popular. Given that more of this trend is among college-educated folks means it might contribute to it beyond it just being attributable to Ozempic.

Good to see for sure!

LA Builder’s Remedy

I’m a huge fan of Builder’s Remedy type legislation. Probably a wholly under-explored way to deal with systemic inadequacies in society (a blog post for the future, for sure!). In March, it *might* kick in for LA, fast-tracking housing developments.

Builder’s Remedy laws kick in at a state level in parts of the US where a local municipality did not build or approve sufficient housing. This allows developers to skip various rules, essentially forcing the local municipalities to catch up with the development of sufficient housing.

I like the idea of Remedy Laws: set a higher level of government that allows local communities discretion as long as they keep up with what’s required and mandated. If they lag behind, the remedy law kicks in, allowing the system to skip restrictions imposed by the local community.

🎶 Music

After watching Rings of Power, I can’t get this track out of my head. Enjoy it!

Bear McCreary (w Rufus Wainwright) - Old Tom Bombadil

Magical.

See you all next week. Since I’m on the west coast of the USA, I’m hoping to see a wonderful sunset. Hope you get to see one too!

Simon

Very inspiring piece, thanks!

I agree with your problem articulation around wealth disparity and the phenomenon of 'privatising gains, socialising losses'. Fewer publicly listed companies and bail outs are expressions of that. At its core a political issue that is hard to solve with tech and culture imo.

I'm less optimistic about meme coins being productive means. Their entertainment utility seems lower than that of say music, art or movies in comparison. But that is debatable I guess. They currently do not contribute utility to any critical goods or services (shelter, food, logistics, health etc.). Do you expect that to change?

Access and broad ownership seems to be easily gamed. Many project initiators create thousands of wallets to fake distributed ownership and social media bots to fake attention metrics. In reality its often just a few people behind new meme launches trying to enrich themselves and some of their friends.

I struggle to see a real community aspect here, let alone signs of spiritual / religious connection like indicated by Murad. Most meme coin projects have a half life of a few hours or days before they go to zero. My definition of a community is a body of individuals sharing norms, values and identity. Why do you think any of those 3 can be established within days? Aren't they a function of time and energy spent together?

Love the analogies you're drawing to sports betting and alcohol.

Where do you think memes might go from here?