Protocol Thresholds and The Days of Two Noons

Also: Building (Housing) Bridges to Nowhere, Congestion Pricing Follow-Up, and 54% Is All You Need

Last weekend, I was in Sacramento for a wedding and during some time off went to the railroad museum.

It was a super interesting museum detailing the history of railroads in the USA and particularly the completion of the first trans-continental railroad. With America connected and rail travel increasing, it became necessary to standardise the time across the United States. Instead of local times set by the sun, the USA was divided into 4 timezones and on November 18, 1883, the day dubbed “The Day of Two Noons”, clocks were rescheduled across the US. Historical archives from papers like the New York Times, describes this day.

At just 9 o’clock, local time, yesterday morning Mr. James Hamblet, General Superintendent of the Time Telegraph Company, and manager of the time service of Western Union Telegraph Company, stopped the pendulum of his standard clock in Room No. 48 in the Western Union Telegraph Building. The long glistening rod and its heavy cylindrical pendulum ball was at rest for 3 minutes and 58.38 seconds. The delicate machinery of the clock rested for the first time in many months. The clicking of the electric instrument on a shelf at the side of the clock ceased and with it ceased the corresponding ticks on similar instruments in many jewelry and watch stores throughout the City. When, as nearly as it could be ascertained, the time stated above had elapsed, the heavy pendulum was again set in motion and swung backward and forward in its never varying trips of one second each from one end of its swing to the other. With the starting of the pendulum the clicking of the little instruments all over the City at intervals of two seconds between each click was resumed. Mr Hamblet had changed the time of New York City and State.

Almost poetic. This kind of process: going from a disorderly, localised solution, to a more orderly globalised solution is something we’ve seen time and time again. What particularly interested me about this phenomenon is the unknown thresholds and second order effects. When they happen, it feels incremental, but it’s actually a much bigger deal.

With the adoption of standard time, it not only improved commerce and the effective functioning of railroads, but it also changed how people relate to time. Suddenly, time took more primacy as a separate idea and concept compared to merely being associated with the sun. On the back of the telegraph coming into commercial use just a few decades before the day of two noons, people could now more readily coordinate to communicate, decreasing the cost of arbitrage of resources.

Another example that always come to mind for me is the advent of 1-bit communications at the turn of the 21st century. While 1-bit communication existed, it was rarely on its own. For example, a telegraph often included more information. A telephone call last longer than a yes or no. As the cost of internet bandwidth and storage decreased, it suddenly became more feasible to consider communicating at 1-bit increments. Pre-telegraph it would be entirely possible to send a letter across a continent with simply the word: “like”, on it. But it just wasn’t done or wanted.

Now, tapping a like button suddenly became a feasible way to communicate, where previously it was unheard of or unnecessary. Before this, one might even ask the question, rightly: why would you want to communicate in 1-bit? But now, much of the web is just a like button, an instant 1-bit intent to say: I like this. At the time of its invention, it felt incremental. But now, most of the web runs off these inferences. A like now turns the gears of the all-encompassing algorithm in the background.

When new technology comes along, I always wonder what the thresholds are that we can’t see, and how this change results in second order effects beyond its immediate use-case?

Railroads needed standard time and now it means that in 2024, my local bagel shop opens at exactly the time it says on Google Maps. TCP/IP was needed to ensure interoperability and now in 2024, Elon Musk decides to make likes private on Twitter/X. In 2008, Satoshi Nakamoto needed a distributed timestamping ledger secured by proof of work to create a global digital currency and now in 2024, crypto twitter is debating the merits of Iggy Azalea’s $MOTHER memecoin.

In Philadelphia on the day of the two noons, the newspaper read:

There was a good deal of interest manifested at the railroad stations and other places to-day in the change of time that went into effect at noon. A curious assemblage gathered in front of Independence Hall to witness the operation of setting the hands forward, and the intent expression with which the spectators gazed at the dial deepened into one of bewilderment when, after half an hour’s watch, no change was apparent on the face of Philadelphia’s principal clock. The delicate operation of adjusting the monster mechanism in the belfry of Independence Hall was performed by William E. Harpur, and occupied just 10 minutes. At the Broad-street station of the Pennsylvania Railroad several amusing incidents occurred among anxious individuals who did not have a clear idea of the change that was about to take place. By the new standard Philadelphia is 36 seconds faster than before.

Not much changed that day for each person, individually. It might have felt like incremental change. But, it inevitably led to vast change. What feels like incremental change right now that is actually a threshold change? There are many days of two noons, we just need to pay more attention.

Bonus Content!

An otherwise chill week for me. Caught up on some films I’ve been meaning to watch. Godzilla: Minus One (loved it!) and Perfect Days (loved it!). Unintentional Japanese double billing. I also started reading Dungeon Crawler Crawl. LitRPG has been growing in popularity and been meaning to dip my feet into it. Also, unlike the atrocious discourse found in social media, I’m enjoy The Acolyte. Looking forward to see where it’s going. Also, recently bought myself the New Balance Rebel V4 running shoe in the hopes of finding a faster long run shoe that isn’t max cushion like the ASICS Gel-Nimbus. I’ve tested it on all run types this week and damn, I really, really adore it. Good as a daily trainer, for speed work, and long runs. Excited to run more in it!

Congestion Pricing Follow Up

I had fun with last week’s newsletter talking about taking cues from EIP 1559 in Ethereum and applying it to congestion pricing. After writing it, I discovered that Barnabe wrote about EIP 1559 from thinking about congestion. There is overlap, indeed.

To obtain the best social outcome, we'd like to operationalise the following idea: any user on the road should pay for the harm it causes other users. By internalising the public harm into the private profit evaluation of each user, incentives are aligned. We do so by adding a toll to the road.

Who you choose to compensate for the public harm, it’s still difficult to determine whom to reward. Barnabe talks about this extensively.

Let’s say we are fine with the dilution: an epsilon amount of cash is better than zero after all. We can level a second critique to the microeconomic argument. We've not differentiated, among our population of Ethereum users, between transaction senders and holders. While transaction senders are the ones inconvenienced by the congestion, holders aren't (by definition, they don't send any transactions). But how should a mechanism determine who has been harmed by the congestion or not? Likely, it is impossible, as we’d need to know who would have sent a transaction but didn’t because of the congestion. Is rewarding everyone who holds ETH with the burn a good enough approximation of a mechanism that compensates those affected by the fee market congestion?

Love, love, love this. One of the reasons I enjoy writing this newsletter is when cross-pollination like this occurs. Go follow Barnabé Monnot!

US Housing & Bridges To Nowhere

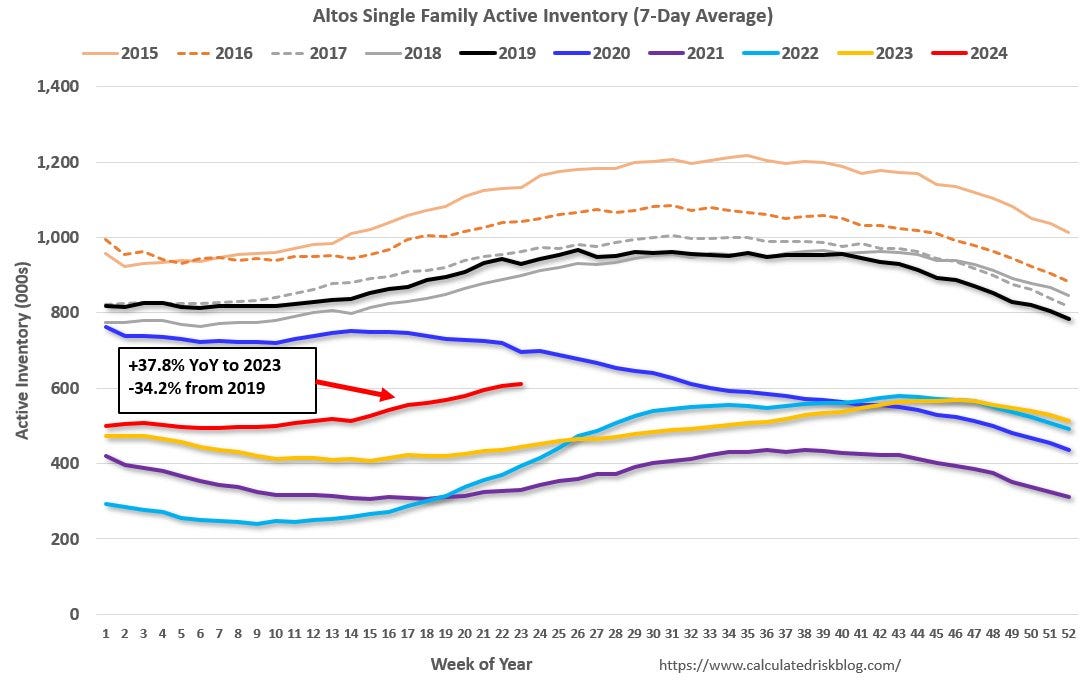

Found this graph this week. It’s still crazy to me just how much the pandemic + growing interest rates shifted the supply of housing in the US.

It just kind of haven’t recovered. This recovery has also been driven quite lopsidedly with places like Austin and Minneapolis driving new supply (that’s also driving inflation down in those cities more quickly than others).

(ignore the click-baity title, it’s actually a good video)

Steve Randy Waldman’s recently article on housing in the US had some great quotes. If you *truly* want to drive down prices, you can’t ultimately just rely on the private markets and deregulated zoning to do so. The market tempers itself. Over time it might eventually drive down costs, but it might do it at a pace that requires a more directed hand in the form of the state.

Unless the government steps in to build when new home sales demand gets soft, we will not add homes to the builders’ demand algorithm. Builders have learned to tightly control inventory by retreating from construction when demand becomes slack. Building more homes is bad business during weaker times... We won’t see the construction boom that people want because the builders are here to make money; they’re not here to fix the low inventory issues of the existing home sales market, which is their main rival for demand.

What the state *can* do, is take on longer-term risks alongside its power as a large buyer. Which means, it can build “bridges to nowhere”.

It’s a cliché that the government builds “bridges to nowhere” that the private sector never would build. That’s true. And it’s a credit to the public sector. Bridges to nowhere are what turn nowheres into somewheres. We need many, many more bridges to nowhere.

It reminded of this famous image of a subway station in China, seemingly being nowhere in particular. In 2017, Caojiawan station opened to a field.

This is what it looks like a year ago.

We should build more bridges to nowhere. We need to build more housing.

Arena Tours Not Selling

Arena Tours aren’t selling as well. Notable acts like Black Keys are struggling. Lots of theories abound. Maybe it is just the economy (tickets being expensive)…

“I’m in Peoria, so St. Louis and Chicago, it’s not too big a drive,” says Anderson, who is 32 and works for a medical supply company. “But between that and pricing and parking, it’s hard to justify even if you love the band. I wasn’t seeing anything lower than like $100 for United Center. I just glanced and was like, ‘Oh, that’s a no.'”

or… Live Nation producing the tours trying to sell more tickets than the acts can play to…

Why would they book such oversized venues? To some extent, “it’s just pure greed,” says a booking agent with many years of experience, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “Live Nation needs to fill these big rooms, so they make aggressive offers and then the agents and managers take them. Some of it is, it’s hard to go backwards. If you’ve ever done arena tours before, it’s very difficult to take a step back and make less money on a smaller tour. No one wants to present that to a manager or band.

…especially if it’s possible that there’s deal between promoters and venues.

Though he stresses that he doesn’t know all the specifics of the Black Keys’ situation, Kurland tells Stereogum, “The reality is that when a big promoter has a deal with a venue, they need to put shows in that venue and they make money on a lot of the ancillaries. Did Live Nation do a tour deal with the Black Keys for this tour? If so, these are probably the venues that they recommended. Did they pressure them? I have no idea. Was it more profitable to go into these rooms vs. smaller rooms? I’m sure that was the case.”

…but, I wonder if there is something else we can point to? On the one side, you have Taylor Swift selling mega tours all over, but the middle-class big acts (is that even a right way to frame it?), struggles.

Someone commented that arena shows are just bad.

Arena shows are inarguably the worst concert experience one can have. I even prefer stadiums/festivals over arenas (and I don't like stadiums/festivals). But of course, small venues and theaters are easily the best.

But, it doesn’t explain why that’s changed. Arena tours aren’t new. Is it a social thing? I remember arena shows when I was younger, in South Africa. It was usually quite rare to have big acts come down to South Africa, and when they did, it was an *event*. Loads of people you knew, went, and it was a talked about social event. Taylor Swift with Eras solidly fits this bill. It’s an *event*.

Is there something else going on? Maybe there isn’t, but it’s interesting to think about. :)

54% is All You Need

I adored this viral quote/share from Roger Federer’s commencement speech at Dartmouth.

Timestamp at 13:20. Essentially:

Perfection is impossible.

In the 1,526 singles matches I played in my career, I won almost 80% of those matches.

But what percentage of points did I win?

54%

In other words, even top ranked tennis players win barely more than half the points they play.

When you lose ever second point on average, you learn not to dwell on every shot.

You teach yourself to think:

'Okay, I double faulted...it's only a point.'

'Okay, I came to the net and I got passed again...it's only a point.'

Even a great shot, an overhead backhand smash that ends up on ESPN's top 10 playlist – that too is just a point.

Here's why I'm telling you this.

When you're playing a point, it has to be the most important thing in the world. And it is.

But when it's behind you, it's behind you.

This mindset is crucial – because it frees you to fully commit to the next point with intensity, clarity, and focus.

If you win 54% of *anything* in life, you’ll make it in anything. If a trading algorithm produced 4% above a coin-toss you will inevitable be a millionaire. You just need to work in an industry that allows you to roll that dice often enough to ensure you can reap the benefits of that 4% over a coin toss.

I enjoy this re-framing because while statistically it makes sense, the idea/feeling of “winning” feels like the initial point of the stat (you need to do 80%+ to be successful), while in practice, it’s the latter (you only need 4% above a coin-toss). If you can afford it, small incremental improvements over years gets you there.

Token Supremacy Critique

People like dunking on NFTs now that it seems like the wave had “ended”. People are writing books on this end just as the dust seemed to have barely settled. I have not read the book, but I did find Charlotte Kent’s critique of it (she mentions my work in it).

Small’s book recounts the two years of media-driven interest and inflation, but omits this backstory and wider scope, limiting readers’ understanding of what that moment was truly about, and thus, where it might be going.

In all honesty, there *is* a lot to critique. A lot of “look at those weirdos being insufferable” energy to all of it. But, there is still a good amount of really stellar and interesting work in the space. I hope in time that this is what remains of this 2021 boom and what the future could still hold.

There’s still too much to art to make! :)

Golden Bug & The Limiñanas - Hi No Tori ft. Vega Voga

The song for the week is a great track with a driving bassline. Enjoy!

That’s it for this week, folks. Hope you get to enjoy a lovely sunset. See you next week!

Simon