On Hardness and The Social Institutions of Crypto

Code is law, but we run the code. Also: music industry ownership, kishotenketsu, and urbanism elsewhere

The original intent was to build a codified and mathematical system that doesn’t include the fallible and messy parts of humanity into the governance of one of our most important institutions: money. In the absence of an established regulatory regime that’s able to contend with unintended outcomes, this appeal to the code is sometimes the last resort of adjudication. “Code is law” is the oft-repeated mantra. Over the course of 15 years, the social side has been under developed, resorting to moving goalposts and amorphous social collectives taking action with various cues, including things like appeals to ostracize taken from Ostrom’s research on managing a commons.

In the UASF (User-Activated Soft Fork) debacle in Bitcoin, the “code is law”, but “we run the code”, forced a group of developers to not raise the block size limit of Bitcoin. In the 2016 hack of The DAO, in Ethereum, the entire network was forked to move the stolen money back to the participants, and since then, it hasn’t happened again. There’s sometimes little rhyme or reason to how these social institutions murmur.

Photo by Rhys Kentish on Unsplash

Rightfully so, this appeal to avoid the social institutions has led to many people avoiding and dismissing the industry (my emphasis):

Regression to the code erodes social norms, and this consequence accounts in large part for what repulses people from crypto. Even as protocols fulfill important social functions like affordable remittances and escape from inflationary regimes, “the space” appears to outsiders as greedy and riddled with scams. It is for this reason that crypto seems to stand apart from all prior human institutions. More than just “lawless,” it comes off as a “normless” zone where morality is suspended, even if the prevailing intention is to support the resiliency of all manner of social organizations.

They ultimately argue that:

The question is not how to add norms or social agendas to the crypto “space,” but how to join crypto with a broader institutional ecology. When we imagine a crypto that is more integrated into social life, we don’t think of an uncorrelated economy accessed through screens, but of non-extractive media of exchange and real value production that are more seamlessly integrated with our daily institutions, supportive of the interactions, organizations, and social lives we already live. These sorts of institutions simply cannot be grown if regression to the code is the only binding rule.

Ending with:

Counterintuitively, the original cypherpunk vision of credible non-state institutions may survive only through contact with cultures more full-blooded than crypto itself. If so, this next phase will certainly require protocols beyond incentives and smart contracts.

I generally agree and I wish that the same fervour to re-imagine the how we can coordinate and build new economics over a weekend can be applied to social institutions. Crypto indeed can benefit from not staying in its own world, but also actively deepening its roots into the day-to-day of local problem and communities.

As Arnaud says about his critique of crypto:

Our goal should be to give small groups the ability to find each other, acquire resources, coordinate, and act without needing the approval of others (and in fact without even needing to make their existence known). This would require building ways for gradual, scoped information sharing while remaining on neutral and trusted coordination environments.

So, yes, this hard-lined approach to keep a blind eye to the social side of crypto is ultimately to its detriment. I understand why there’s an icky aversion to it: the belief that once we make it messy, it’s a snowball back to the systems it was made to avoid.

However.

While critics often wonder and ask as to why it feels weird that crypto is worth $2 Trillion in 15 years and it hasn’t felt like it has made the mainstream impact that it’s ideologues had hoped for, it neglects and dismisses just *how* these protocols are supposed to make an impact. They are not tools that are supposed to help you today. Today, they can only make promises.

In VGR’s essay on “In Search of Hardness” referencing Josh Stark’s idea of “hardness”, Josh points out that hardness as an aspect of information comes from the goal to make the future more certain.

Call this property hardness.

Human civilization depends in part on our ability to make the future more certain in specific ways.

Fixed, hard points across time that let us make the world more predictable.

We need these hard points because it is impossible to coordinate at scale without them. Money doesn’t work unless there is a degree of certainty it will still be valuable in the future. Trade is very risky if there isn’t confidence that parties will follow their commitments.

The bonds of social and family ties can only reach so far through space and time, and so we have found other means of creating certainty and stability in relationships stretching far across the social graph. Throughout history we have found ways to make the future more certain, creating constants that are stable enough to rely upon.

The law and our modern institutions attempts to make the future more certain with an appeal to a monopoly on violence (alongside other social norms). Blockchains attempts to do this with p2p cryptography and code.

Any introduction of a system that attempts to make things “harder” takes time, because legitimacy is a social institution. A handful of people can read the math, cryptography and the code of Bitcoin and Ethereum and “see” the hardness, but its ability to be trusted as a form of hardness is through the act of socialising and legitimizing it over time.

It’s why there’s this appeal and “regression to the code”, because while in the short-term it erodes social norms, it hardens the legitimacy of the protocol to enable new forms of social institutions on top of it.

But modern protocols are more than that. They’re not just engineered hardness, they are programmable, intangible hardness. They are dynamic and evolvable. And we hope they are systematically ossifiable for durability. They are the built environment of digital modernity.

Crypto as a technology is only 15 years old. It can’t even vote yet. If a new nation state or a group promising a monopoly on violence with universal suffrage over it were to spawn today, how long does it need to exist before it is actually trusted to maintain its legitimacy? Institutions are trusted precisely because they take time and that can’t be avoided. Harder protocols attempt to give that certainty in the absence of existing social institutions.

And so, over time, it’s expected to be what we see. A messy back and forth between the protocols and the people. The code is law, but we run the code. Our assessment of the strength of the hardness can only be judged by time. And that means that the order of work and change can take years and some of the problems only surface after enough time has been spent relying on these protocols. The north star is always an attempt to give back agency through the reduction of the cost of coordination.

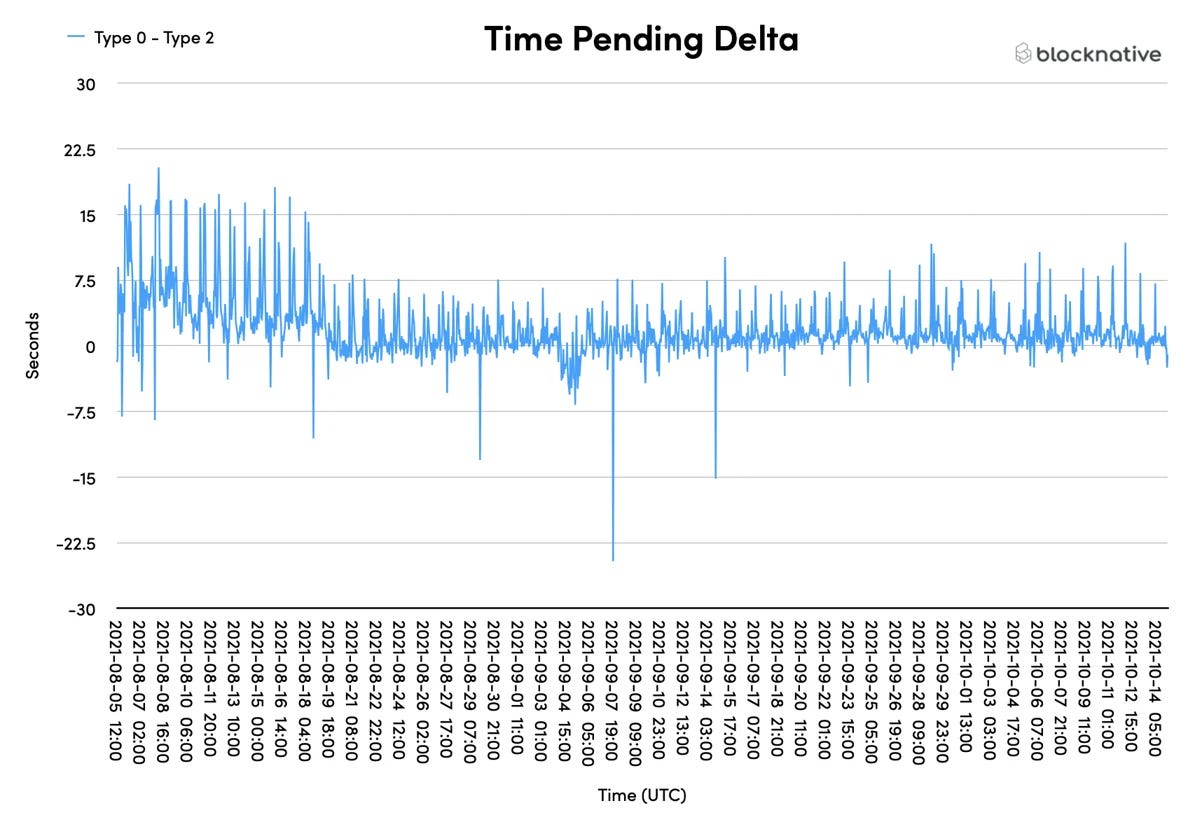

A really great example where it took time was the EIP-1559 fee market change.

In order to use a blockchain, a user has to send along a fee, paying for the infrastructure. The miners take all the transactions and (for the most part) selects the ones paying the most fees and creates a new block in an allotted time from it. If there’s more demand the price goes up because there’s only a certain of transactions that can be included in a block.

Because there was no nexus for this market, a user had to basically guess what the fee should be. Wallet software tried to help the user here by monitoring all the recent and pending transactions, but it was essentially an awkward, blind social game, that sometimes meant that users overpaid for transactions and/or their transactions got endlessly stuck in the queue, because richer users could cut the line.

The EIP-1559 essentially protocolized the fee market by adding limits on what users could charge and limiting the extent to how much the fees could rise and fall, block by block. It was designed such that the user (mostly) doesn’t have to set the fees manually anymore. They don’t have to guess. And the transactions usually get confirmed fairly soon after if they are willing to accept the current proposed fee set by the protocol.

What once was a messy social auction was replaced with hardness that ensures that the cost of this social game is gone, allowing users to spend their social energy elsewhere. It’s been lauded as a big success. Here’s Ethereum’s team lead’s comment on it.

It was first proposed in 2018, and only implemented in August 2021 (12 years into the existence of crypto). It takes time.

A contract is an agreement to not defect from mutually desired behaviour. In legal systems, you can always defect at a cost. In crypto systems, there is no option to defect once you opted into it. Both attempt to induce certainty about the future. Another great example is the popularity of automated market markets: enabling trade without the social cost of maintaining an order book that only started seeing the light of day around 2017/2018.

Ultimately, this push and pull between the code and the social side is a dance. If enough agree, there is always a last resort of dismantling it through social decisions. Just don’t run the code.

All this is about attempting to reduce the cost of coordination across certain domains. In reading In Search of Hardness, VGR alludes to Claude Shannon, and I think it’s apt.

The Shannon-Weaver model details the cost of noise in communicating. One such noise and source of entropy is time: our desire to communicate with the future. While we might see language as the primary way we communicate, we anchor towards our society’s various laws, norms, markets, and architecture to communicate in ways that flapping our lips at each other, can’t. It’s context turtles all the way down.

So while this regression to the code can seem normless, there’s still active conversations and social institutions being born from a source of hardness that we did not have before. For example, memecoins might look like a bunch of degenerate gamblers playing money PVP against each other, but you’d miss that all of this is only possible because a conversation is happening in the first place. Try as we might, language only gets so far. We wear the band t-shirts and buy a token because of what it says to ourselves and to others around us. And this too can only be enjoyed through time. Dancing is only enjoyed through time (hey, there’s a pun here somewhere between Lindy Hop and the Lindy effect). A conversation only happens through time. A song is only enjoyed through time. Just hanging out, after all might be seen as the bliss of human existence or a waste of time.

So while it’s true that the social institutions of crypto is lacking and often messy, I think it’s ultimately better judged as a social institution not today, but a few decades from now. It doesn’t mean that we must accept the various normlessness behaviour. There’s lot of shit that should be called out. It doesn’t also mean we should always “regress to the code” because ultimately the best protocols should serve the people, not the people serving the protocol.

The harder job is maintaining this dance without it unravelling prematurely. In any good dance, there’s tension both into and out of it. Crypto protocols that are too social too soon can become what it was supposed to avoid. Too rigid, too hard, too “code is law” too soon and it loses its legitimacy due to its perceived normlessness and serves no-one. In both cases, it will unravel and we’ll lose the friends we made along the way. Let’s keep this dance going.

via MidJourney, trying to get it to make hard pet rocks made out of cryptography 😅

Bonus Content!

A bit of a busy week for me as I finished up an art project and travelled to South Africa. I’m spending much need time with family (and the summer sun!), so I suspect the newsletters over the next few weeks will be a bit shorter than usual. I’m also getting back to working on my new novel. Fun!

At least we get snow here in DC! Made me really happy!

Urbanism Elsewhere

Netherlands is usually one of the countries that people point to wrt good urbanism, but this thread details some lesser cities that shine.

It does tilt quite heavily to European cities. While subjective, wish it showed more Asian cities too. :)

Solano County Plans

You know, I always treat any investor that wants to start a city with skepticism and hesitation. The recent proposal for Solano Country from a bunch of Silicon Valley VCs, however, do feel like they are treating it with the kind of urbanism I enjoy. I love that they are specifically calling out the urbanism of Japan and Barcelona.

The California Forever city plan relies heavily on the lessons of Japanese urbanism and Barcelona’s superilles to lay out a street grid that is fully connected while still defining areas where the streets are safe and comfortable places for people - a hybrid between 19th century grid pattern cities and superblocks. There are no sacrifice zones. Every street will be a great place to be. We think the California Forever street grid proposal is a novel contribution to urban planning in America.

I would actually reading/watching a proper urbanist’s take on their proposals. If I find something, I’ll share.

Who Owns The Music Industry

As a result of these shifts, the shape of commercial power in the music business looks quite different, and much more crowded, from 20 years ago. Major music rights holders and tech companies are now expected to generate profits for a dizzying array of stakeholders sitting outside of industry borders, including banks, private equity firms, big-tech conglomerates, and sovereign wealth funds — not to mention public retail investors.

Kishotenketsu

A while back there was a lot of discussion on Kishotenketsu on Twitter, and the comments incorrectly referred to kishotenketsu as a conflict-less narrative. I thought that was wrong as it’s about how the narrative is structured rather than what the narrative is about.

Counter Craft had a great essay on this.

For writers, I think is useful to think about different structures to remind yourself that there isn’t just one way to think about these things. Hollywood screenplay guides can at times be ludicrously prescriptive, but other conceptual structures like kishōtenketsu exist around the world. The real question is what structure is generative for you in any given project?

I once wrote on Kishontenketsu back in 2019, and oddly, it’s the one blog/article that has the highest amounts of SEO juice still on my blog.

Inwards - 19TET (Varsity Star Remix)

Love this gentle, hazy electronic track. Feels like it can be for a summer sunset or a cozy snowy winter’s day.

Enjoy a sunset, friends! I know I will. I’m in the sunset capital of the world (South Africa).

Simon

I was inspired by a poor (generational poverty) group of kids in Montagu (Klein Karroo), Web3 Art, artist Willie Bester and your bonding curve to create a framework (model) for a new digital art ecosystem. The goal of this ecosystem is not profit but to create a breeding ground for Web3 artists. The challenge is to "make the money work" and this is where your bonding curve comes in as the primary component of the financial scaffolding for the model. Another possible component is leveraging (through arbitrage) each South African's travel allowance(s) (the Currency Hub biz model).

This is essentially a new model of "love-work" built on a foundation of the three human rights (being, belonging and becoming), that leverages raw potential (artistic creativity / talent), defi and Web3 technology, to satisfy the needs of our emerging future as human beings.

Here is the link to the ArtStoke website https://artstoke.co.za/artstoke-commons/1192/

or a direct link to the model (PDF) https://drive.google.com/file/d/1WPgMThzQ9r13jonnLgXbLiJMbLAX1cbo/view?usp=sharing

Would love your thoughts and some pointers?